Mobilizing the Neck and Spine (part 2)

Like so many explorations, I have a personal connection with neck issues. I got crunched once quite solidly in a rugby ruck and felt a terrifying lightening bolt go through my body. My neck hasn’t been the same since. Then, just a few years back, I slept on the floor and woke up pretty much incapacitated. There was a shooting pain radiating mid-neck down, and any movement caused and 8/9 out of 10 level of pain. I received a few acupuncture treatments that caused a downgrade to a 5/6, but mostly I just laid on the couch and freaked out. All I did was sleep on the floor. What the heck happened?

As it healed, I reflexively moved it a lot. The stiffness sucked, and I didn’t want to go back there again. I stretched and mobilized it often, and even figured out how to make my own ‘adjustments’ or ‘pops’ (both actively and passively). The acupuncture notes first showed me the connection between the wrist and the neck, and why when I flexed my wrist I could get a much deeper stretch:

My chiropractor (which I see much less often) has since nicknamed me “Gumby Neck”, but as all ‘bendy’ people can attest to, more flexibility doesn’t necessarily translate into less pain.

It is the usability and control of your range of motion that matters.

When considering why the neck is either under-utilized or over-utilized in the first place, we have to look at functional movement of the spine to which it’s connected.

Contrast this mastery to my best attempt:

There’s lot’s of hinge points that clump together. I’m unable to get controlled motion at all of my vertebrae, and my neck/upperback is downright stuck together.

It makes sense to have neck issues when you don’t have articular independence.

My excessively mobile neck has to make up for my underperforming cervical-thoracic junction.

Interesting enough, Sue Falsone recently released this video ( a free excerpt from her DVD) highlighting separation of the neck from the upper back through upward and downward dog. I took it one step further in asking the neck to flex — opposite of what the t-spine was doing:

Note that most of the movement in the ‘butt-up’ position comes from my shoulders, not my thoracic spine.

In asking neighboring joints to do opposing movements, you force independent joint function.

To find the specific segment/movement that causes you trouble, you can use Controlled Articular Rotations (CARs) to pinpoint the trouble spot.

CARs Protocol:

- Take a deep breath into the belly

- Push the air into your deep, lower gut and hold it there

- Irradiate tension from that lower abdomen out to every place in your body EXCEPT the one you want to move

- Create the largest, most controlled circle with the joint that you can, keeping the same speed and being conscious of any ‘bumps’ in the circle

- If there’s an opening angle pinch — the angle that’s getting bigger — train through it. This indicates a “tissue issue”

- If there’s a pinch in the closing angle — the angle that’s getting smaller — stop to stretch/use isometrics to convince the brain to allow you the range. This indicates a neurological issue.

Thoracic Spine CARs

Extension, by comparison, is my most limiting factor. You can also see how the veins in my neck buldge when I forget to breathe when trying to ‘force’ movement.

Cervical Spine CARs

As with the thoracic CARs, I choose to perform them from the triangle sit (knees wide, feet together) position to take out any cheating by the hips. Standing CARs tend to have much more variability for error.

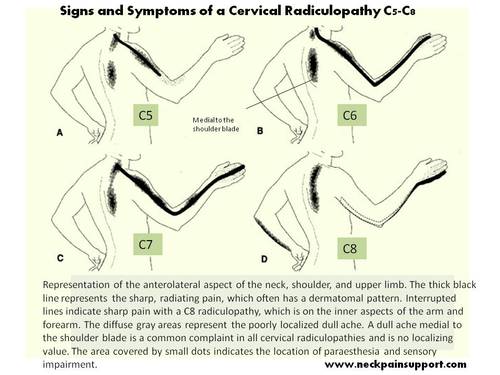

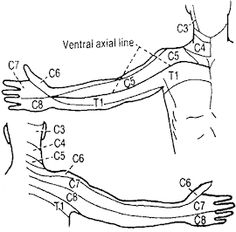

Many folks, including myself tend to have a mobility issue at c5-c6. This is where I got ‘crunched’ the first time and where the pain radiated from the floor sleeping debacle. Located almost mid-neck, it serves as a primary nerve point. Patterns have reasons behind their repetition. If you’re willing to keep digging, you’ll usually find something.

Hinge Point Training

Hinge point training focuses movement at a particular vertebral junction. You’re looking to flex, extend, and rotate at that specific spot.

You can perform this type of practice supine on the floor, or from the same low triangle sit as before:

Segmental Cervical Spine

The chin tuck attempts to create space in which to move in. My flexion is also a bit off. I should have tried flexing from the mid-neck, not the lower neck.

A closing, short angle pinch calls for some stretching or isometrics. Whichever you choose, it should be as precise as the movement used to assess it.

Segmental Cervical Stretch

Palpate the spot, lean into it, and bend away.

In systemizing movements, we have a means of using distinct inputs to create distinct outputs. Pain is a result of trapped tension. To release it mechanically, we have to be able to capture it in order to disperse it elsewhere.

TO REVIEW:

- The neck is a translation of the spine

- Articular independence must precede articular interdependence for efficient movement

- Asking neighboring joints to perform opposite tasks is a practice of autonomous function

- CARs can be used to assess joint range of motion and pinpoint a trouble spot

- Hinge point training can be used to practice motion at a particular vertebral junction

- Once joint independence has been established, it can be integrated into a larger movement pattern

Part One of this series, Relaxing the Neck, can be found here.

**Credit for much of the information presented here goes out to Dr. Andreo Spina and his Functional Range Conditioning seminar.**

Christine,

Much respect for this info you are presenting. Great quality.

One question:

Can you explain a bit more into the CARs technique specifically referring to the extension movement of the neck. I’m a bit cautious/skeptical about that movement as I’ve always learned to be wary of neck mobility in the past and trying to understand this new approach to articular care. Many thanks!

Dave, Thanks for the positive feedback.

I think neck extension is often a vulnerable, don’t-want-to-go-there position, which is why practicing this movement is so important. You first need to recognize where the extension is coming from. Is it the same vertebrae that is constantly flexed forward? Could it be likely that because you’re extending from this ‘flexion point’, extension is extremely uncomfortable? Can you get flexion and extension above and blow this primary motion point? This is where CARs can come in so handy — the slow, deliberate circles minimize threat maximize motion. Don’t venture past a 3 out of 10 on the pain scale. Are you familiar with opening and closed angle pinches? Have you explored how the protrusion or retraction of the chin affects the pattern?

I think? Is it that chin retraction allows for more breathing room for soft tissues ( such as arteries, lymph nodes, nerves etc.) within the cervical joints while in neck flexion? Does that mean that it is the same for neck extension(retraction as a protective protocol)? or, is it that one should inversely perform neck protraction while performing neck extension? I would definitely be interesting to learn more about this particular subject as I personally haven’t come across a definitive source addressing of this concern. Maybe there is a link to an article either you have written or someone else that particularly addresses this concern? I think any technique attempting to tap into this lost ROM should address this concern as this new technique seems to go against convention wisdom ( at least at a glance).

Concerning opening/closing angle pinches, I have read some of your work that has mentioned it, such as the following excerpt from your “exploring CARs post:

“An opening angle pinch signals a tissue problem. Work through it. A closing angle pinch indicates there is a biomechanical problem. There is a structural or neurological glitch. Forcing it can cause further damage. Specific stretching or release would be the protocol. In general, keeping a slow, steady speed ensures that you are in control. Loosen the tension as you come across a speed bump and continue through with deliberate practice.”

If there is more to the opening/closing pinches concept/protocol, than I am unaware of such and would be interesting to learn more.

FYI, I am registered and waiting to attend a FRC seminar in the fall, but am trying to gather as much understanding/experience about these concepts prior, so that I can bring some questions with me to the seminar. I just don’t want to accidentally hurt myself in the process because of attempting to build experience with these movements without proper understanding of all of the necessary safety techniques.

Thanks for the response!

Yes. I feel I must begin replies to comments with ‘I think’. Information is based on interpretations, and questions directed to me must be rooted in my perspective of the issue at hand and possible solution. My answer to you would be “play around with jaw position and neck movements” to see what works for you. Some past work I’ve read for a jaw-neck connection can be found here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QtH7lQrPoxU , here: http://www.sethoberst.com/articles/category/neck-and-jaw, and here: http://www.drdooleynoted.com/anatomy-angel-jaw-protrusionretrusion-and-center-of-mass/. (If you’re interested, I began a small reddit about a year ago where I post most of this stuff, which is searchable by subject: https://www.reddit.com/r/StartMoving/). A big part of any training is awareness. If you are deliberate and fully conscious of your movements and something doesn’t feel right, you stop. I would never encourage a wrote protocol void of personal monitoring and feedback. Your body is smarter than I or even Spina could ever hope to be.

As far as the pinching goes, directions given at the FRC were turn to Functional Range Release if there’s a closing angle issue, but is this really a viable response for the vast majority of the population? Again, personal exploration of the spot in question should become a routine option. Nobody can feel what’s going on in your tissues better than you. Safety becomes a need when people can’t interpret their own feedback. It really wan’t touched up on during the FRC seminar or take-home paperwork.

Great response. I couldn’t agree more with your points. Thx for the links I will definitely check em out. I agree as well about the internal feedback priority in regards to self-awareness. Where this issue differs, is with instruction/classes/coaching. How does one, as an administrator of this system, ensure their participant carrying out the movement is safe? While I definitely think this is where experience and attentiveness are a huge factor, this is one area where I do like to look for helpful cues to assist the mastery process/progression involved with these movements. I imagine movement screening is synergistic with this line of thinking.. Thanks again for the response.

I believe it begins with teaching awareness. When working with someone (one-on-one) there is a constant ongoing conversation. Where do you feel this? Do you still feel it there when we change this? Does this make things easier or harder? In essence, you act as their brain and constantly promote attention and feedback. Soon enough, they’ll begin mirroring these thoughts and words and assessments back to you, with amazing explanations as to why! In a class setting, you would need to build in places/ pauses for exploration. Rotate, turn, shift, roll, etc. Model the behavior but encourage them to find their own sequencing and solutions. I think of it very similarly to meditation practice, except the body is thinking and searching for answers.