Living Up to Expectations

When I was freshly 20 years old, a guy named Pete Steinberg told me to get on a plane.

I’d been playing rugby for a few months and he’d spotted me at a regional tournament. In three weeks, a developmental team was going to tour the UK and I was supposed to book a ticket and come up with $1000 to play for the USA. It all happened very fast. There was no time for questions; only directions.

The trouble is, I didn’t have a thousand dollars. I don’ t even think I had a hundred. The only person I knew who had it was my Dad, but he liked to keep his money close. The Bank of Serafino was all savings and no loan. Still, I had my directive. Even though I knew what the answer would be, I had to ask.

I dialed the numbers, waited through the rings, and finally heard him say hello. I spoke slowly as I tried to best recount what had just happened. When it came to the asking, I let him off the hook. I acknowledged it was way too much money to play a game across the ocean. Somewhat defeated, I finished my monologue and waited for the inevitable.

There was a pause.

And then this man who still works fifty hours a week in a screw factory said what I never expected him to.

“Who do I make the check out to?”

In that moment, everything changed. Rugby became far more than this game I simply knew as get the ball. It was going to get me a passport and life-changing experience. It was going to get me this honor of wearing my country’s uniform in a foreign land where I would stand with my hand on my heart while our national anthem played. It had gotten my Dad who had never seen me play to invest two weeks pay into his belief in me.

When you are expected to be good at something it seems like there is no other choice but to be good at it.

For the next nine years, I devoted myself to the game. In those formative years after college, I made a move across the country, and my only contact was the local rugby team. I told them some teams I’d been selected to and got an immediate reply. Because of rugby, I wasn’t going to be alone. Then I blew my knee out, and I found myself very much alone. All through rehab, I imagined climbing back up to reclaim my place. I got smarter and learned strategy. I dug into everything I could get my hands on regarding physical therapy and biomechanics. Nothing ever seemed to be enough.

Like all players who can’t imagine their lives without a sport, I got into coaching. It was a volunteer gig that paid nothing but I let it absolutely consume me. I was teaching at the time, but mostly assigned independent work so I could come up with drills to make the girls at Western Oregon better. I still wore jerseys and rugby themed t-shirts to school. The kids would ask what it was and I would tell them. I brought rugby into PE and we played for hours in the rain. I swear, for a few years, no one at the high school knew my name. They called me, and I responded to, this seemingly magical word of “Rugby.”

As you can imagine, this had to end and it wouldn’t end well. The girls I was gifted into coaching eventually graduated and were replaced by a group who didn’t have that same spark of interest and ability. No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get this new group to show up consistently, let alone care. As my coaching passion waned, so did my desire to keep playing. Everything hurt all the time. I couldn’t even bend over to put the balls in the bin at the end of class. Every other aspect of my life was being robbed to keep this semblance of identity going.

A hard couple of years followed. My jerseys were packed away and the kids were corrected into using my given name.

I turned away from everything that made me great and special.

Without them I was ordinary and regular. As I reluctantly accepted this new fate, everything in comparison seemed less than.

As I reflected on my past, I realized I never chose any of it. People outside of myself claimed this is who I should be. They expected me to do and be, and because I didn’t have any expectations of my own, I assumed they were right. This seemingly small revelation was my turning point. I looked at the decisions I had made for myself with a renewed sense of intention and promise.

Slowly, I began to invest in the things that I held off as footnotes in my rugby story. I started writing a health curriculum that reflected the questions I was seeking within myself. I created my own text and workbook. In PE, I stopped copying what the other guys were doing and built a program based on movement and developmental motor skill.

When I looked up from my work and in on others, I realized what I was doing was very different. Traditional means no longer suited the majority of needs. I wanted to make the experience of learning individualized. I used my personal struggle as the blueprint for evoking change.

I stopped training off of programs meant for the USA Eagles and switched my focus to rehabilitation. As I got rid of things I didn’t need and focused on things that I did, my body felt better than it had in a decade. I was able to do stuff with it. So much more than participate in rugby. And I could teach it to others. That sense of specialness returned and the sadness of lacking departed.

For a long time I demonized the game that brought me so much, because I couldn’t figure out how to be a part of it. It was all or nothing, and circumstances pressed me to choose nothing. But work is never wasted. What makes you good at one thing can carry over into something else. You just have to be able to dissect your interests and realize your talents can apply to more than one thing.

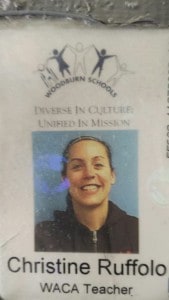

This is the badge I wear everyday, and it tells a much better story of who I am:

We are sold on the illusion that heroes are better than guides. Guides, however, understand that investing in people, not skills, is how heroes are made. They don’t set expectations, they listen to them. They look beyond current actions and capabilities and try to make the hero see that his contributions can be multifunctional. Being able to adapt safeguards survival.

Redirecting your talents doesn’t make them any less significant. It keeps the hero purposeful and invested in their own cause. The things that served you well in the past are the same things that will provide you continued motivation in the future. As you make the transition and justify your changing thoughts and attitudes, remember that what you love simply gives you the opportunity to practice greatness. You define yourself, and special is as special does.