Examining the Forearms

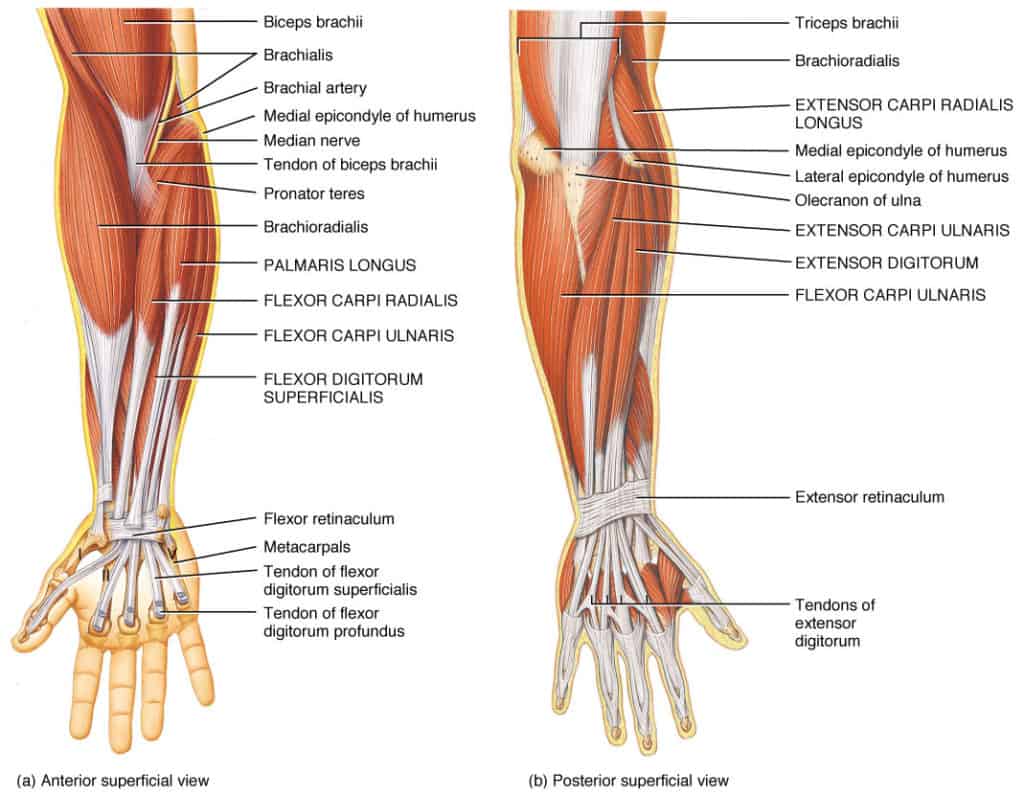

Limitations in the wrist are the Achilles heel of push dominant training programs. Repeated gripping and hoisting of bars and bells turn the hands and wrists into one trick-ponies that get cranky when trying to press the body off the ground. Investigations of the wrist, though, kept leading me back to the forearms. Serving as the meridian between the elbow and the fingers, it’s distinct musculature is responsible for the vast and intricate movements of the hand:

Very few muscles reside alone in the hands. photo credit: anatomy-medicine.com

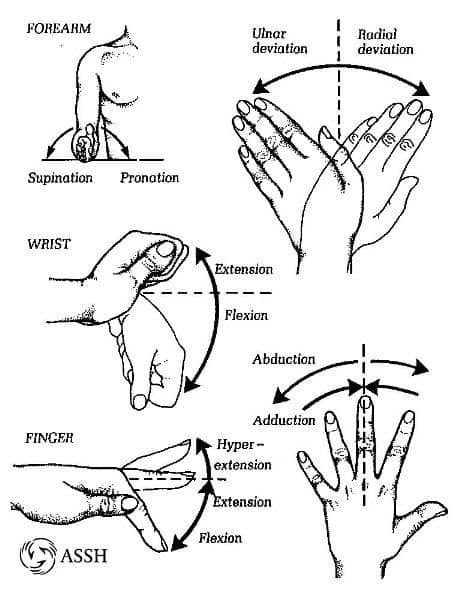

Movements of the forearm, wrist, and fingers:

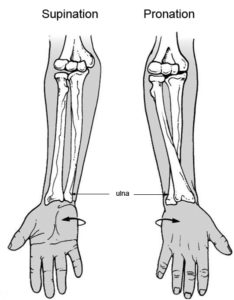

Note that rotation is NOT a listed motion of the wrist. Supination and Pronation is caused by movement of the radius around the ulna:

Note that rotation is NOT a listed motion of the wrist. Supination and Pronation is caused by movement of the radius around the ulna:

photo credit: wikifoundry.com

photo credit: wikifoundry.com

Mobility of the wrist, then, is directly related to your degree of supination and pronation. A lack of forearm rotation puts more strain on the wrist to perform movements, and wrist movements cannot be isolated unless rotation of the forearm is nullified.

FOREARM MOVEMENTS – wrist acts as extension of forearm

Bent elbows effect the forearm very differently than straight elbows. Supination is assisted in flexion, while pronation is hindered:

You can also use the ground to rotate the lower arm in a closed-chain fashion — the forearm stays and the body moves around it:

This example is focusing on supination. Pronation would shift the body/shoulder to the outside. The plank position can easily be swapped out for lying on your stomach, hips resting on the ground.

Load, particularly the offset design of kettlebell, can be utilized to perform eccentrics to either side:

The same principle could be used for elbow CARs and PAILs and RAILs.

If you’re curious about what a straight armed manipulation might look/feel like, this stick move showed particular promise:

Wrist adduction is my non-googled description of ulnar deviation.

WRIST MOVEMENTS – wrist acts independent of immobilized forearm

Here’s an example of open-ended wrist movements using Dewey Nielsen’s brilliant cell phone feedback mechanism to minimize forearm influence:

By extending the fingers throughout, you minimize misleading finger motion. First maximally flexing, extending, and laterally shifting gives your brain a picture of how big the ‘circle’ can be, and that these are the movements combining for the circular effect.

Another option would be to use the ground to act as a forearm stabilizer, slivering the motion into segments of extension and flexion:

Maximal ROM in ulnar and radial deviation becomes very apparent when the hand has help staying flat.

FINGER RIGIDITY – Creating wrist leverage over interference

As mentioned above, wrist movement can often get mistaken for finger movement. Stiff fingers act as a buffer to this glitch, and their firmness extends into the hand to create a longer point of leverage for the wrist to pivot from. The stopping point was repeatedly dictated by tension in the forearm:

I tried keeping the elbow straight throughout, using only the wrist as a fulcrum. Keeping the rotation steady was the hardest part. When I intended to rotate the forearm and move the elbow pocket at the end, it took every ounce of concentration to try and achieve this with an extended wrist.

TO REVIEW:

- Look to the forearm to alleviate problems in the wrist

- Wrist movement is directly affected by forearm rotation

- The wrist does not rotate; what seems like rotation is actually a combination of up, down, left, right

- Supination rotates the thumb to the outside (typically palm up)

- Pronation rotates the thumb to the inside (typically palm down)

- Most practiced movement tends to begin from an already supinated or pronated position

- Forearm movements with a flexed elbow act differently than those with an extended elbow

- Find ways to keep the forearm flat to isolate the wrist

- Stiff fingers also stiffen the hand, creating leverage to help mobilize the wrist