ACL rehab – thinking beyond typical protocols

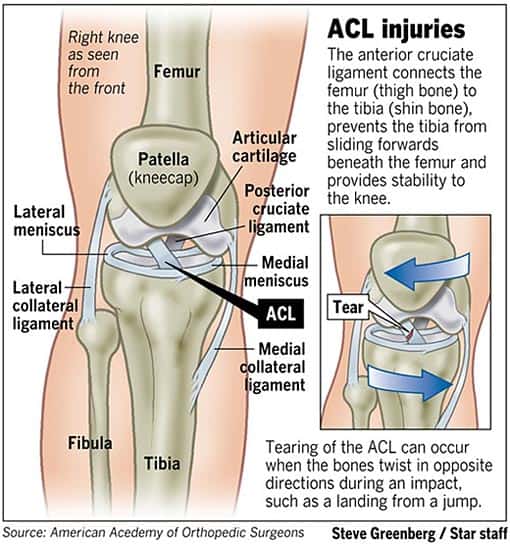

I suffered a partial tear of my left ACL in 2003 during a rugby match. There isn’t a cool or gruesome backstory involved, just some open-field running with the ball. One cut and down I went. And stayed down. It might have been the only time in the history of my playing career I didn’t care what happened to the ball. An ER visit revealed it was a partial tear. I had a tour of New Zealand coming up in a few months, but I also had a knee brace and some duct tape. I was not going to be left off the roster or out of the experience.

Maori women don’t get blasted off a ruck like American women. Those amazing creatures don’t move. Needless to say, I tore things a little more. Surgery was in the works. My passport stamped and my once in a lifetime experience over, I was ready to let a surgeon fix me.

The process just wasn’t as thorough as I had planned.

I was to have a hamstring graft put in to replaced the damaged ligament. They took an ‘ apparently inconsequential’ piece of my hamstring and made me a new ACL. I went to physical therapy for about eight weeks, and once my knee was functional in terms of the scientific standards of the day — a certain amount of flexion and extension in an isolated and unloaded simulation — I was released. The trouble was, I still couldn’t do much of anything, and I didn’t know where to turn for help.

If only I knew then what I know now. My dissatisfaction with the way I was left led me to a career in rehabilitation. The following list represents five often overlooked movements that have made all the difference in the way my post-op knee feels and moves. Hopefully this compilation can help others fast track and solidify their road to recovery.

1. Treat the skin of the superficial scar

The skin is the outermost layer of connective tissue. Since all tissues are connected, restrictions there have effects elsewhere. Scar tissue is filler tissue, but it can still be receptive to force inputs, and the surrounding cells can still adapt. Whether it be through needling or the grasping/rolling technique shown below, mobilizing the skin goes a long way to manipulating the layers underneath.

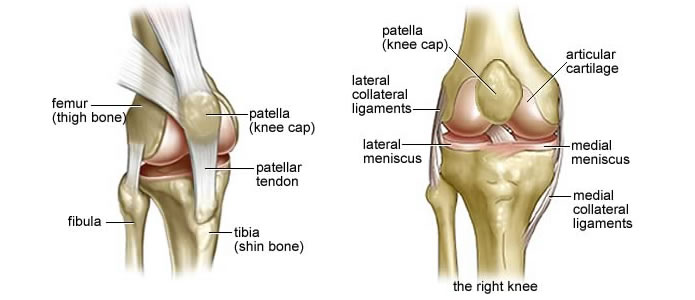

2. Mobilize the kneecap

In extension, the soft tissues are lax, allowing for the patella to free-float. The knee cap of your reconstructed knee will not move as easily (in all directions) as your ‘normal’ knee. Encouraging it to do so with consistent mobilization will take one more non-performing variable out of the equation.

3. Practice Tibial Rotation

The tibia should have about 15-degrees of rotation through the ligamental arrangement of knee. A lack of tibial rotation, particularly internal rotation, is a common compensation to foot/ankle issues and surgical knee repair.

A necessary requirement to biomechanically sound deep squatting, the movement itself can be used to assess each leg’s amount of tibial rotation:

If one side’s found to be deficient, tibial rotation can be driven mechanically, being manipulated and held with your hands while integrating this motion into a larger movement pattern:

You can also lock the thigh and fully dorsiflex the foot to unload the pattern, ensuring that the anterior tibialis (big shin muscle) moves in sync with the foot and tibial tuberosity (knee bump):

A small ‘X’ has been marked just below the reference point – the tibial tuberosity.

Finally, you can partially or fully load tibial rotation through lateral wall squat rotations:

Lateral shifting of the hip leads to forward rotation into the wall. The lower leg assists this movement by internally rotating. Knee bends throughout. A fully loaded single leg pattern would involve lifting the outer leg off the ground and having the inside leg bear full body weight.

4. Get hamstring isolated full knee flexion

For those of you who’ve had ACL reconstruction from a hamstring graft, this one’s of vital importance. Since a piece of your hamstring was removed, hamstring function, primarily knee flexion without the use of the calf/ankle, gets disrupted. To isolate the hamstring and practice motor control in this pattern, maximally point those toes and keep them pointed throughout the duration of the movement:

The second part of the video is taken from a foot-elevated glute bridge.

Isolated hamstring progressions should consider short (heel close to butt) and long (knee barely bent from straight) positional work, 10-15 degrees short of maximal. The half-kneeling terminal (end range) knee flexion is a challenging example of short hamstring function:

Notice how Dean does not get his foot fully pointed and initiates the first rep with the ankle.

There’s also a pretty huge connection between hamstring function (short) and dorsiflexion. Without the ability to fully flex and get heel to butt, the ankle can’t fully dorsiflex (pull top of foot to shins without taking the heel off the ground). The following picture is a visual showing the discrepancy between my right (‘normal’) and left (reconstructed) ranges of active (brain-only) hamstring flexion.

Uncoincidentally, I also have more plantar flexion (toe point) and less dorsiflexion (toe pull) on my surgically altered left side. This makes my right leg the driving force for any actions requiring dorsiflexion, such as getting up out of a deep squat:

Note how much smoother the movement was when I manually pulled my lower leg into further knee flexion.

I also believe that a lack of hamstring function contributes to the growth of an excessively large ‘knee bump’. The bony protrusion of the far knee is quite sensitive and is often a point of irritation:

A hamstring unable to keep the lower leg from shearing forward would put constant strain on the patellar tendon — pulling the cells of the bone into a higher tibial tuberosity. Direct hamstring work calms discomfort in this area each and every time.

Finally, combining full flexion + rotation + load = a dynamic challenge of all compromised functions:

The bottom (left knee down) video is much more wonky — I easily get another repetition in the time allotted when using my right knee as a pivot.

Sidebar: a lack of hip internal rotation is a huge risk factor for potential ACL injury. For specific hip internal rotation exercises, try these.

5. Integrate full knee extension into multiple hip positions

An exit ticket for most knee rehabilitation programs is the ability to fully straighten the leg or get full knee extension. What is not often evaluated is how well you can perform this movement with various positions of the hip — most notably multiple degrees of flexion and extension. Getting terminal knee extension is just as much a function of quadruped contraction as it is of hamstring release, and ability to do in all available angles of the hip makes for a more thorough assessment for ‘back to activity’ readiness.

Band Resisted Knee Extension with Hip Extension:

Knee Extension with Full Hip Flexion:

TO REVIEW:

- DO NOT be satisfied with what medical professionals deem as ‘repaired’. If it doesn’t feel right, it’s probably not right. There is always something you can do to improve function, either through the brain (motor control) or tissues (force-tension).

- The skin and kneecap can be manipulated much like tendons, ligaments, and muscle.

- Isolated hamstring function requires pointing the toes through full range of motion.

- Don’t forget about practicing short and long positioned hamstring contractions

- Most injuries occur through knee rotation – the least trained movement possibility of the knee

- Practice knee extension from multiple angles of hip flexion