Developing Your Own Movement

As a young athlete, I did whatever my coach told me without asking questions. I rewound video tape of Michael Jordan again and again to get the footwork right. As I aged, I accepted and attempted to perform summer programs with cleans and snatches listed first, and performed them dutifully even though I had no idea of whether or not I was doing them correctly. I did what I was supposed to do, what all the best ones did.

Mimicry was simple. I wanted to work and put in effort. That was always my calling card. As long as I had a what, the how and why didn’t matter too much. The list of tasks developed my arsenal and toughness. Thinking took too much energy. All I needed was a pump-up playlist and a workout sheet. If doing was the essence of being, I was going to show up everyday and tick all the right boxes.

Like many, it took major and then chronic injury to challenge this identity I heralded. The goal went from higher squat numbers to getting into my car without pain. The rote physical therapy worksheets weren’t helping. I was doing everything exactly as I was told, and not getting any better. Perhaps it was how I was moving that was faulty.

Re-creation is an important first step in creation.

Practicing Jordan’s up and under led me to develop a left handed flick shot, that was much faster than a hook and caught opponents off guard. Wild cleans and snatches made me realize I was quad-dominant and needed posterior chain work (and a lot of it) before attempting to utilize these into my programming. For the first time, I recognized going backwards could be as satisfying as going forwards. Staying put and hanging out a while can even be the most delightful of all.

I haven’t always thought of movement as an art, but I do now. I watch dancers with awe instead of analysis. I can separate the two. Movement is beautiful, not ferocious. There is wonder in every joint and position. When I describe what I do as play my intent is not to belittle it, but to impress upon the value of personal exploration and experimentation. Believing the possibilities are endless gives repetition less and less appeal.

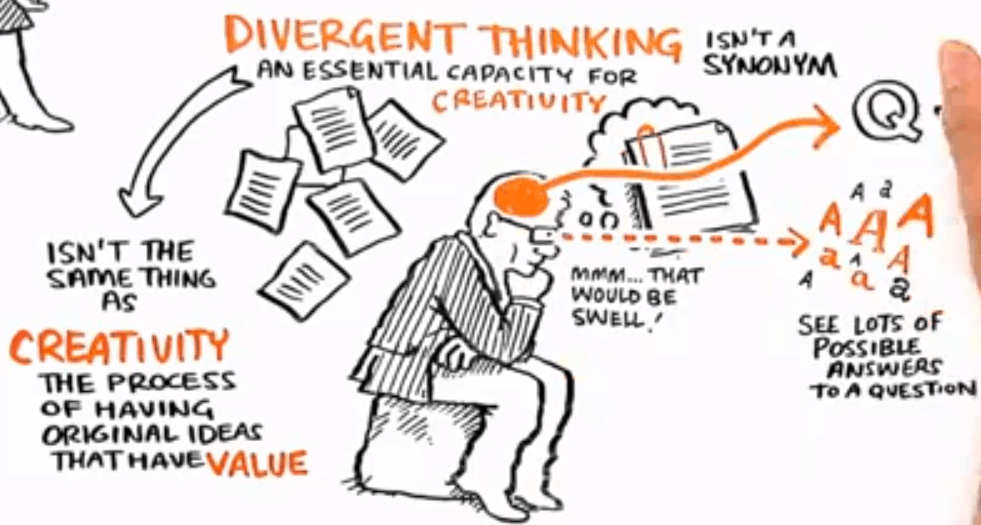

Making something novel isn’t the same as revealing something novel. I don’t think anything can be invented that wasn’t here already. The perspective and introspective journey is what’s different. It’s what you can claim as your own and be proud of. The passage from question to answer to another question is where confidence grows, because the dialogue is all internal.

Personally, my entire training revolves around creating. I have no plans when I walk in what I will work on, nor how long I will stay. I base everything on feeling. Whatever feels tight or neglected or subpar is what I tinker with. I leave with a sense of stimulated accomplishment much different then the wiped-out exits I made in my youth.

Though the change has taken years, these three things can infuse a little play into your practice right now:

1. Schedule it in.

Write it into your current sets and reps schemes. Grant yourself the time and pace to adapt by integrating exploratory work into your current programming. Nothing’s too small here. A grip change or head turn can be inspiring if you can actively be aware of the changes it causes.

2. Problem solve.

Seek out movement puzzles. They force you to think, and more importantly, stick with the thinking process of trial and error.

3. Interact with someone or something.

Put yourself in an environment in which you are not accustomed. Use boxes. Attempt to climb a tree. Manipulate objects. Reacting and reacting with intent are separate entities. Use practice in the former to develop the latter.

Physical shifts come from mental ones. The most wonderful thing about becoming more playful is that its value lies in the here and now. The surprises and learning happen in real time. Einstein said, “creativity is intelligence having fun,” and the man played with quantum physics. Observe a child or baby and I think it could be extended to developing intelligence. As a matter of fact, I don’t know of any type of play that doesn’t involve movement. Still, exercise of the brain gets continuously reserved for thinking and meditation. Imagine what you could come up with if you combined the two.

Chris,

Your posts get deeper and deeper. Consider writing a book. You’re onto something big.

Thanks so much for this. I actually am, but attempting to distill exactly what slant it should take. When it gets finished, would you be up for a critique?