Pulling Chest to Bar

Pullups. The bane of every chubby kid’s existence. We were strong, just not relatively strong. We liked to stick what we were good at, which was moving things other than ourselves.

Eventually my weight leveled out and I was drawn to things that asked me to hold myself up. Externally rotated hangs led to supinated grip up and over the bars. When my palms faced forward, however, I always got stuck around bar to neck level. The elbows just stopped around ninety degrees. Trying harder seemed to freeze things more. A puzzle of ability without access was in my midst.

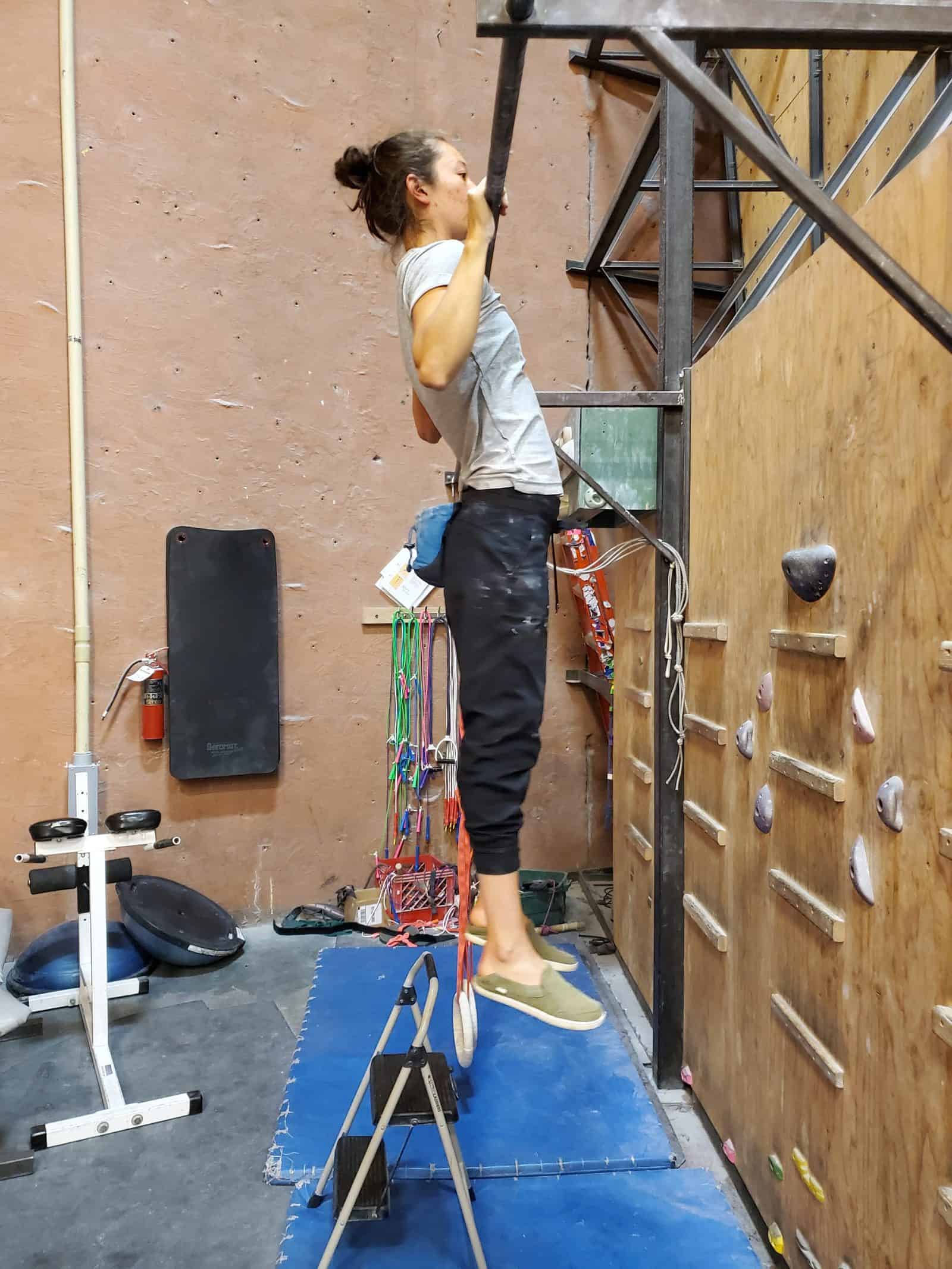

Other than the success I found when I simply turned my hands around, I knew that I could support myself on the bar through joints as distal as the wrists:

Where was the error when I grabbed the bar with my hands?

Since the issue seemed to stem from how I held the bar, I started exploring there. I didn’t quite know it at the time, but the larger plan was to reverse engineer the troubleshoot, and follow the thread of causation from the outside-in. The following investigations occurred in more spirals than sequence, but will be presented in a linear format of distal to proximal.

1. Grips and Angles

With what part of my hand/ fingers should I hold the bar? What position should my wrist be in? How should the angle of the forearm/ elbow most assist with the vertical pull of gravity? What do I feel the backside musculature doing when things feel right/ easy?

Calluses indicated that I was only utilizing the outside of my hand.

The tension differential disclosed I was using my right side more than my left.

I used a lateral index/ middle finger pull to help set the scapula and feel strength in the pull. It was test-retested through the ease of a two-finger lean back hang:

2. Scapular Depression and Hip Position

Pulling pronated, my neck disappeared. This did not occur supinated. I had to learn how to create downward force with the shoulder blades depressed. Moved scapula meant the tension moved with it. I needed to keep the internal rigidness lower, more central to my midline. Hip position, even supported through the ground, helped with this. Flexed hips pulled my center of mass forward, and I flexed at the hips anytime things got difficult.

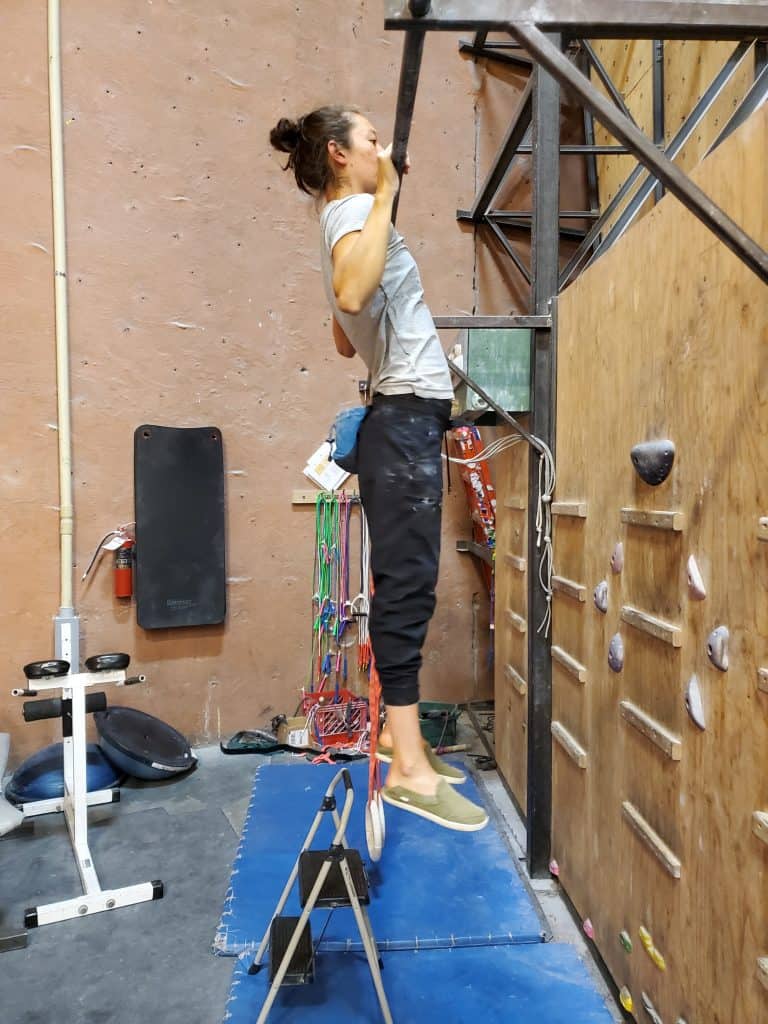

The most effective training position came from tall kneel, hips extended. I set the bar higher so I could extend my arms, and used the less supportive tops of feet/ toes to offer lessened ‘push’ through the ground.

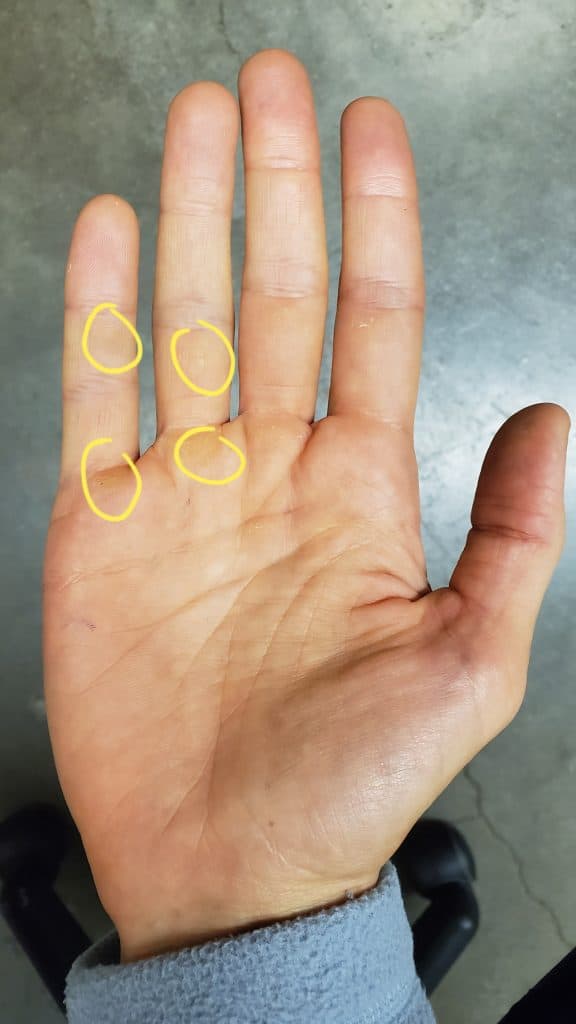

Examination of what the hips were doing revealed a lack of cohesion between my top and bottom halves. When I deadlift, my upper body knows to stiffen to help the legs do the work. When I pull and my feet are freed from the floor, in open chain, my legs just dangle there, acting as dead weight.

This becomes glaringly obvious when compared to a fully connected puller:

Low mid-back point of arch. Heels aligned with head. One piece.

High mid-back point of half-arch. Heels aligned to bar. Two pieces.

I had to get the scapula lower and the surrounding tension to wrap all the way around my lower back, as if it were hoisting me up. I couldn’t quite physically articulate driving things down, so I took the route of lifting things up.

3. Pushing/ Reaching Ribs Up to Bar

Pushing up into a solid surface was something I could understand. My legs were the drivers of the effort ( and I could act as one piece). The beauty of the following front squat set up is that I could place my hands on the rack support and push down, assisting in dropping the scapula. As my hands moved to the bar I simply tried to keep the internal sensation constant. When I lifted my feet I could stay there.

My first big a-ha moment.

Translated to reaching for the bar above my head, I could lengthen that sweet spot between my ribs and hips. Furthermore, I could connect the front and back of my body by reaching with known tip toe into unknown heel:

Still certainly some flexion at the top, but a definite breakthrough.

Perhaps everything is really a reflection of resting posture.

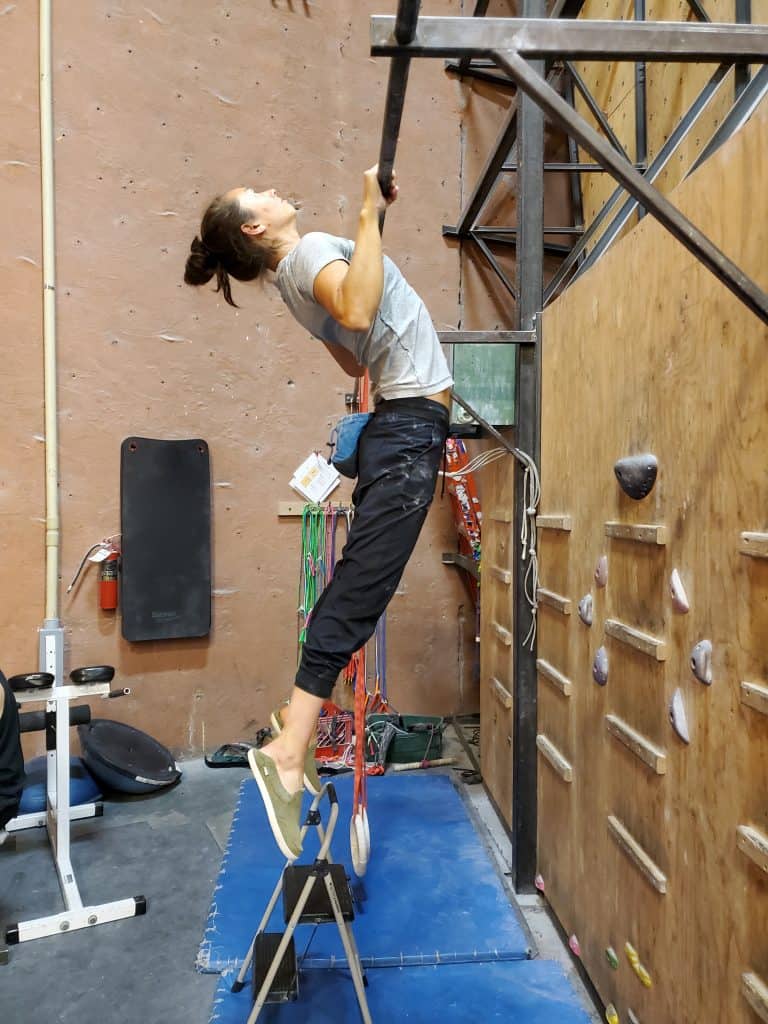

The model puller shown, Nicole Uno, has laid out this concept both logically and beautifully here. Notice it looks like she’s standing at the top of the pull:

I’ve been aware of my posture issues for some time, and it’s taken consistent efforts (both in and out of the training arena) to start to get a handle on things. Posture is subtle. It needs a whole bunch of delicate inputs for things to start to become automatic. Your resting position influences everything. If flexion is the default for when work gets hard, extension is the mechanism that will lead you to ease.

https://www.instagram.com/p/B2EgUjWnY8W/

Understanding the how’s of posture is a lifelong pursuit.

One last piece of evidence on the power of ‘ordinary things’ — the body will lift or lower based solely on breath:

View this post on Instagram

Going up and down simply with breath. #hang #breath #align #useeverything #thinkmovement

It’s never the big pieces of the puzzle that stump you. It’s the tiny, detailed ones. As you search for context to fill the gap, be aware of your fixations. Sometimes we need to change the lens, others, simply adjust the zoom.