A Different Way to Use, Train, & Treat the Knee (Part 1)

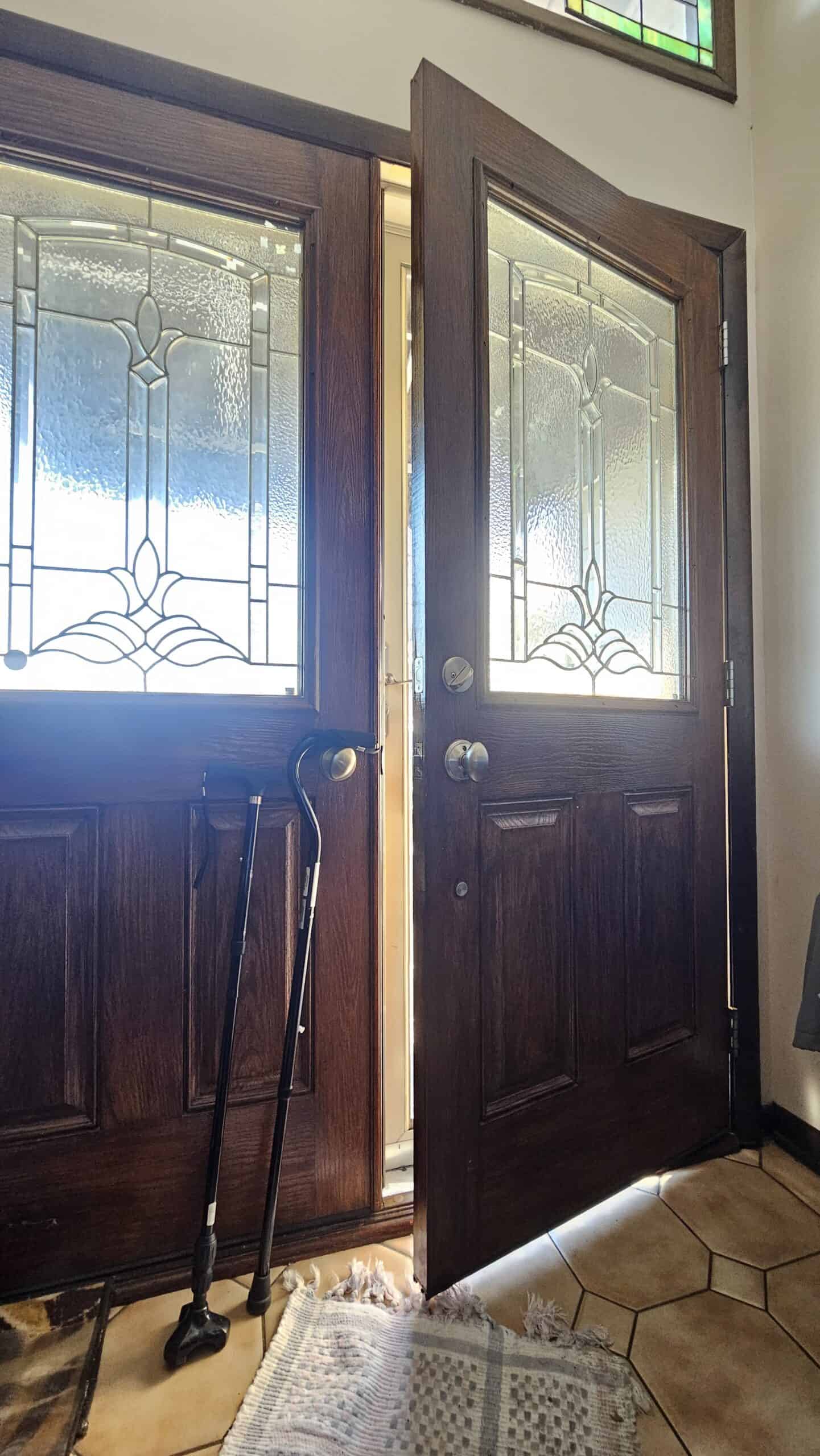

There are three hinges on the feature photo door. It’s a strong front door, solid and meant to take some battering. The cheaper, lighter, all-have-problems-closing-and-opening doors inside the house have only two hinges. Weight-load divided by two, or weight-load divided by three. Things move and function better the more the action gets dispersed.

If we look at the number of joints in the leg, the vast majority lie below the knee. Much has been made of the split in the shin and in particular tibial rotation, but it’s the tibial pitch that actually moves the patella:

A primary principle, then, is to keep the tibia moving. The following hopes to give you some ideas about how to do this, and some build-up options to try when you cannot.

Concept #1: Use the Knees as Gas Instead of Brakes

Using the knees as the joint that holds you up is akin to only having one hinge on the door. Similarly, using the knees as the primary means to STOP you from moving (aka braking) would warp the joint and the entire system. Releasing the knees, otherwise termed as ‘collapsing’ or ‘buckling’, uses the hips and the feet/ ankles as load bearing weight support. The middle hinge is temporarily removed and the frame relies on the top and bottom hinges to hold the structure:

People with knee issues struggle with this. Pain, whether chronic or acute, prohibits movement as a protective mechanism. The nervous system is constantly seeking out safety, and safety is better generated by hanging on versus letting go. (Consider how someone who struggles with balance finds a way to locomote and get around.)

When I first learned this technique (from Adarian Barr), it was linked to developing speed and linking fast feet to the stumble reflex. I quickly connected it to knee extension, building trust and safety in the opposite, so I had a continuum of actions to fall back upon:

View this post on Instagram

Though I have not had knee issues for some time, (likely because I choose to expand my understanding mentally over push my body physically) I happened to have a client with knee, hip, and back pain to test this on. He was trying to resume his semi-pro basketball career, and when I asked him to jump, I noticed the knee lock up upon landing:

View this post on Instagram

He had been dealing with this issue for years, and the only guidance he could get from team physios was isolated discrepancies in minutia such as hip rotation. No one saw (or potentially looked for) the knee jamming up the hip. It stopped so the body crashed down on top of it. He only had pain upon landing, and the landing is where the knee function changed. On take off, he was able to drop the shin down, push off and swing the leg through.

He was a bit frazzled by his inability to knee release, so we broke things down step by step, building safety and security at one level before progressing with the next. We started with full wall support and getting the knees to go forward, then used hands on ladder rungs to drop, then removed the ladder and incorporated release into a run start, finally removing the flat ground to test the operation of the system in an unstable environment.

Please note that the toes don’t clench (a sign of lack of safety up the chain) and the head and neck also release when the system is able to let go. The hips create a circular arc that drops and hinges back to the start position.

Part 2 of this series will look at using pressure to subsidize movement when the nervous system won’t allow the knees to collapse.

Part 3 will examine how the angles of feet and knees can be manipulated to create space for the tibia to keep moving.