Meaning, Behavior, & the Social Element

This piece serves as a follow up to “The Problem with Meaningful Phys Ed“.

Amidst a pandemic, the question that kept driving what we did and how we did it was, “What matters?” Weirdly, and almost embarrassingly, this did not drive the curriculum prior. It was better defined by exposure. In a school year that was fully online for 3/4ths of the year, the new and strange circumstances required a rethinking of purpose and need.

Other than COVID-19, Oregon was hit with massive wildfires and a paralyzing ice storm during the 2020-2021 school year. It was crises on top of crises. You know what doesn’t come to the forefront of teenage minds during a prolonged period of stress and instability? Exercise. When you are in survival mode and cut off from everything you know and rely on, the instinct is to shut down and conserve and brace to keep existing.

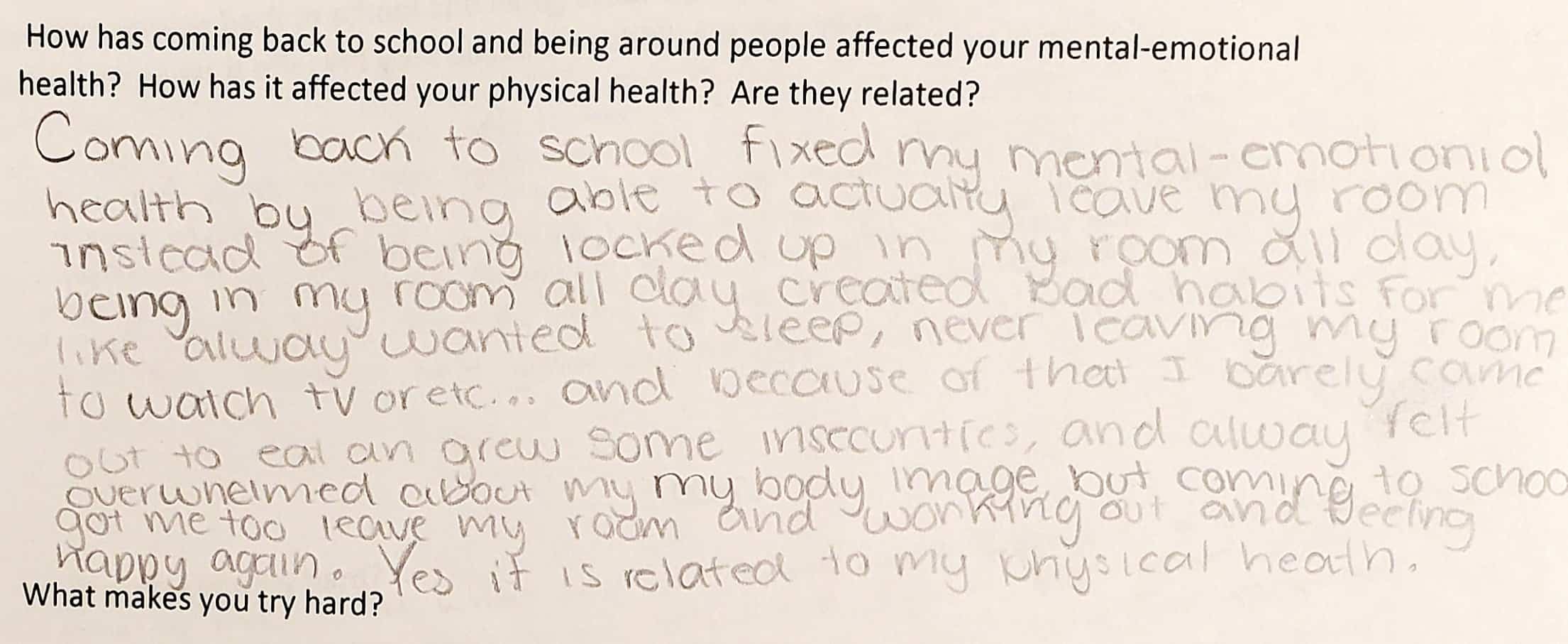

How anxiety and depression show up in the body became the bulk of our zoom conversations during semester one. During quarter four, students had a choice whether to come back to school or to stay online. The mornings were for in-person instruction and the afternoons (post lunch) were reserved for comprehensive distance learning (CDL). The different groups and teaching formats both required and asked for different things.

I am steadfast in my belief that learning is most meaningful when it’s interactive. For the CDL group, their daily assignments asked them questions about themselves — how they used their time, what they valued, what they wanted, how to build consistency — as well as offered up both physical and mental emotional practices they could either fake trying or actually engage with. Even if they didn’t attend the zoom, even if their black squares stayed silent, they had to put thoughts from their head into a form. The interaction was an ask and answer about themselves.

In person, it became very clear that they got up early and came to school to be and play with their friends. We had ‘traditional’ PE, sans the dressing down. We played games and built skills and competed and cooperated. We did this in pairs and we did this in teams. The last thing any of us needed was to be on chromebooks while gathered together in the building.

Both groups were centered on building autonomy. In a compressed culture where almost everything was optional, how do you go about setting up the most effective number of opportunities to shepherd a positive outcome? Furthermore, what interactions are you basing your next steps off of? In a class size of sixty, not everyone wants to offer input. Mostly, it seems, they are waiting for a peer to agree with.

I was listening to a Seth Godin podcast recently, and he was referencing the Provincetown Helmet Insights he observed in 2004. When a couple was renting bikes, they ALWAYS made the same choice regarding getting a helmet. Either both wore helmets or neither did. He assumed that people must be attracted to people with a similar sensibility about helmets.

“It turns out that what actually happens is this: a couple stands at the rental desk and the counter-person says, “do you want helmets… they’re a dollar each.” One person starts to answer, but glances at the other. Then a subtle form of bullying starts.

Usually, one person says, “no, I don’t think so,” and the other, who was about to say yes is intimidated enough to say, “me neither.” Sometimes, it works the other way, “Oh, we’d never ride without helmets,” says one, and the other agrees.”

They have to make a decision to be responsible for a decision.

So how do you steer them into making a decision?

Online, I used click-button surveys (multiple choice) to accumulate responses. Keeping things as easy to participate in as possible kept the feedback coming over a large swath of students. (When able, ‘IDK’ was typed in for those unwilling or able to contribute input). Generalized options were narrowed down into only two possible answers, and the rift between the red and blue piechart pieces told me where to go (or at least where to start).

In person, after the first exciting couple of days, the hand raise votes seemed to collapse into a collective whatever. A singular question shouted out into the crowd only received a few bold and invested replies. Then I figured out how to collect them individually. They each had these ‘been cleared’ COVID stickers that showed they successfully went through the intake checkpoints. These ended up on the gym floor and so they were collected on giant sheets of paper. As I came around and asked for them to stick their dot to keep our floors clean, I privately asked for their response to an either/or direction for the day. I did not accept “I don’t care.” I stayed and waited there until they cared just a little more about one.

Tapping into what kids care about is how you reach them. It’s how you connect and form a shared meaning. It’s about relationships. You to them, them to others, they to activity they chose (or chose not) to participate in. When it’s OK and even necessary to do nothing, can you still find value in the human behind the behavior? Can the class be more than a vehicle of compliance? Do you hear and see what’s really happening, or are you simply affirming your own expectations? When you make it clear that they are what matters, a mutual alignment always occurs.

We just have to remove the artificial pressure of time…