The Problem with Performance Training

I define performance for the purpose of this article as, “the peak execution of a skill at a particular point in time.” Though sometimes cooperative, there is most often an element of competition involved. For most athletes and artists, the bulk of performance comes from practice — doing the thing you are actually trying to get better at. Those looking for that ‘extra’, however, also incorporate performance training: blocks of additional exercise that are supposed to give them that edge. How quickly they are sold on this. How cultural that more equates to better.

The problem is that people fall in love with exercise and let it bias their perception.

The goal becomes getting better at the exercise. If they can just master this controllable thing, they’d be set. But the exercises keep changing. And when they are finally conquered, they are given something else to expose a weakness — not in their skillset but in their athleticism — the most nebulous realm of measurement because most of it is made up. I am not sure how bench pressing 225lbs reveals how good of a football player you are, but average people really like to talk about it. For them, benching 225 is an approachable mark they can hit. Exercise is accessible. Being a professional athlete is not.

Performance training is the equalizer; we get to do what the elite are doing. Our growth in a particular exercise allows us to experience exceptionalism. Challenges are created to make us struggle, overlaid with ill-used hype-words (such as ‘neurological’, ‘plyometric’, ‘imbalance’, ‘proprioception’) that justify them, and we become intrigued by success at the task. Surely improving at one thing will carry over into another.

Athletes aren’t good at asking questions or thinking critically. They do and try hard. They are excellent workers, but they struggle to connect the dots. They believe what is shown to them and ‘looks athletic’. They are driven and willing, almost desperate to find ‘the thing’ they haven’t tried yet to get them over the hump. They are the readily influenced, placing themselves at the mercy of tele-bombing influencers that succinctly show you the just how sure they are.

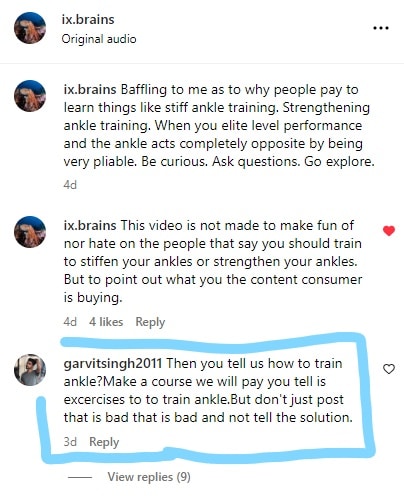

A recent instagram exchange from Adarian Barr highlighted the mega-gap between those wanting to know and also being unable to see:

Consider your take on what was just presented. Now let me show you a comment:

He SHOWED what the ankle was doing. And still there is an angry frustration about a secret being kept. The idea that the movement is the exercise was lost on him. [The actual post with full comments can be found here.]

He then doubled down on his theory, giving brilliant examples and concluding that doing the thing will always offer you more than exercising around the thing:

[Full IG live discussion can be found here.]

One more note. There is a reason athletes and injuries go hand in hand. It is unnatural to keep going and ignore signals that something doesn’t feel right. Yet this is what we are taught to do. The robotic nature of training dulls our senses and limits our perspective. Because pain is a validated hindrance to performance, it’s something we are willing to pause and take care of. We become acutely sensitive to it and numbed by it at the same time.

Performance training makes us the hero of our own story.

The training montage of the underdog working really hard makes us root for them. We can see ourselves working hard. We too, can overcome and find ourselves the victors. It’s a compelling narrative, and there’s absolutely nothing wrong with it. Simply be wary of letting it blind you. What you don’t see or understand might still exist, and be hiding in plain sight.