Kids & Able-Bodied

There is an assumption that young people are able-bodied. It is the gift of youth, the privilege of being newer to this world designed to break you down. It has become incredibly apparent, though, particularly in this last semester, that a troubling trend of exhaustion is (unironically) at play. Just because their parts work doesn’t mean they are functional. Just because they are supposed to doesn’t mean they will.

One class was exceptionally unenergetic. About a fourth of the kids would sit out every day, a mix of both boys and girls. When I asked them about it, they would say things like, “I get so tired after lunch”. [They did not eat.] Lots and lots of “I don’t feel well”. One could chalk things up to excuses and ‘laziness‘, but that dismissal sidesteps understanding and further investigation. These were not singular acts of defiance — it looked, acted, and spread like an actual plague.

Not blaming the kids also meant that I didn’t treat them poorly if they didn’t participate. Modeling that kindness is not reserved for the compliant was important to me. It respects their choice (and evaluation of state) as much as their humanity. They showed up and expressed a need. This isn’t what gets graded, and yet, I feel, is exactly what should be measured and evaluated.

A junior girl who used to be an athlete but has since rejected that identity was a ‘chronic sitter outer.’ It started about halfway through the semester, and she developed a ‘mean girl’ attitude that she extended to her friend. I let them try on this new persona without much feedback. One day they came into my office to see if I had a cup. I said I did and asked if they needed two. They replied yes. I told them I had cold water and asked whether they would like some. They paused for a beat and looked at each other. I could see the surprise on their face. I imagined them thinking, “we’ve been an ass to this lady and she’s hooking us up.” Sure, they said. The leader took a sip while still in my office, closed her eyes, smiled, and said, “Oh my God, thank you.” Her friend said, “yeah, thank you,” and took her sip as she walked out the door.

That was the end of any friction between us. They have been cordial and kind ever since (though still hardly participated). They don’t have to do what I say for us to be friendly. When asked on her final reflection whether she feels she is able-bodied, she replied, “I suppose somewhat since I go to the gym and since I’m very active running around with kids, yes, I am an aunt of 5.” Come to find out she’s been the primary care giver of these kids for months. I suppose if I had that kind of responsibility at home I’d opt out of football, too.

I defined “able-bodied” for them as, “your body can do what you want it to do.” In this particular class, 46% said no. I was floored. In the other two classes that I asked, 34% and 18% also said they did not consider themselves able-bodied (even though general participation in these classes was much higher). Still alarming numbers. Perception shapes reality.

Another question asked them to explain why they sat out if it was more than a few times. “I’m exhausted all the time” was the number one answer, followed by “poor mental health” and “emotionally drained”. This is not a one-off instance to shrug at. This is a troubling trend.

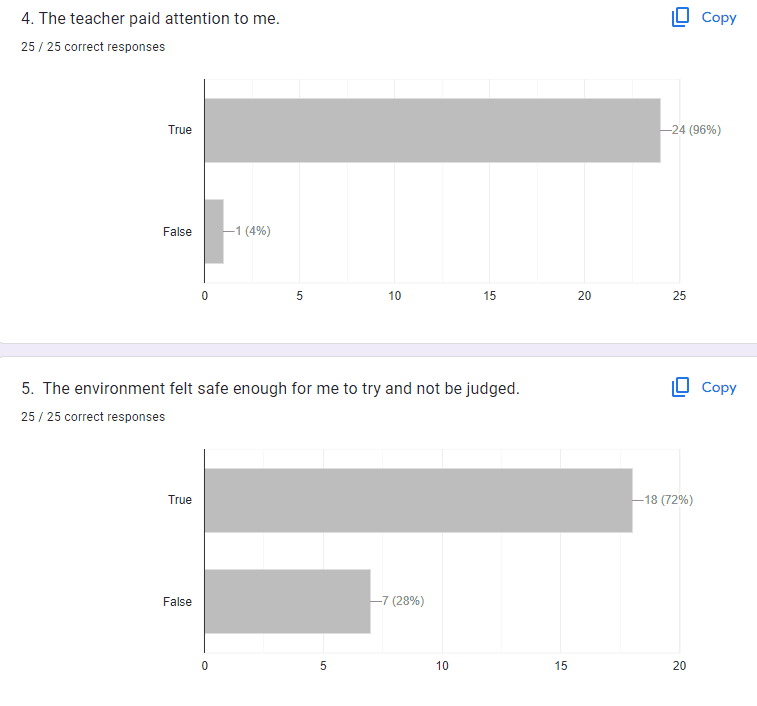

What was also interesting about that remarkably high ‘unable’ class is their judgement of whether or not the environment felt “safe enough to try without being judged.” 7/25 or 28% said it did not. This was much higher than the 13% and 3% of the other two classes (the still considerable 13% had a population mixture of mostly jocks and athletes, whose skill separation was a likely entangled element.) I do not know whether this sense fed into their perception of able-body-ness, or whether it was a result of it, but it remains a coupled premise worth more probing and consideration.

One final note on the variability of perception. Throughout four classes, only one student responded that “the teacher did not pay attention to me.” It came from a student who said that she didn’t participate because, ” i am a complete emotional wreck and i can not do anything without almost crying.” Before class every day she would come into my office and tell me about her troubled life, and I would listen dutifully. Once every two weeks she stayed in class, and the other 90% of the time she went to the mental health office. I say this without malice or bias. Just facts. I wonder what paying attention to her might look like, and how that might change the way she feels.