Relationships, Part 1: Parents

Part One in a four-part series of relational examinations.

The family is your first introduction into relationships. They are the constant you are surrounded with, the base in which all other units are compared. The two people that set the rules in how “together” looks, feels, and acts are your parents. They each had a role, either taken or defaulted to. Unpaid and often unthanked actors, they carried on in the best way they could figure out, tapping into every last ounce of resource and resourcefulness.

They really try, don’t they? They do and they sacrifice and we take what we are given and then we ask for a little bit more. We are trying to find the line. They are trying to find the line. And if they have more than one, they have to figure out how to treat each the same. How can you treat each the same?!?! I don’t treat my friends the same. I don’t treat my pets the same. I don’t treat my parents the same. Same isn’t equal. We do the best with what we know, and for a very long time, I did not know my parents. I only knew what they did.

Dad went to work early and came home late and was justifiably exhausted so we mostly left him alone. He paid the bills, made sure we had everything we needed (and a few we wanted) and basically absolved any worry that we wouldn’t be provided for. I understood how necessary this was. Security is vital. I absorbed a lot of this mentality: the worker supplies and thus deserves rest.

Mom took care of us. She was there. We could count on her being there. She did stuff with us: we played, went on vacation, colored Easter eggs. She was the impetus for the extra — the living past survival and tapping into enjoyment. We can also have a good time while we’re here. These are the two halves I inherited. I valued stability more, because the excess allowed for the extra to be had.

I’ve never really fought with my father. He didn’t ask for anything. I did have a period in my teens when I did not get along with my mother. She always seemed to be asking. She needed help because she was basically raising us and taking care of the house on her own. You don’t think of these things as a kid. You only notice who takes your time and disrupts your chosen state of being.

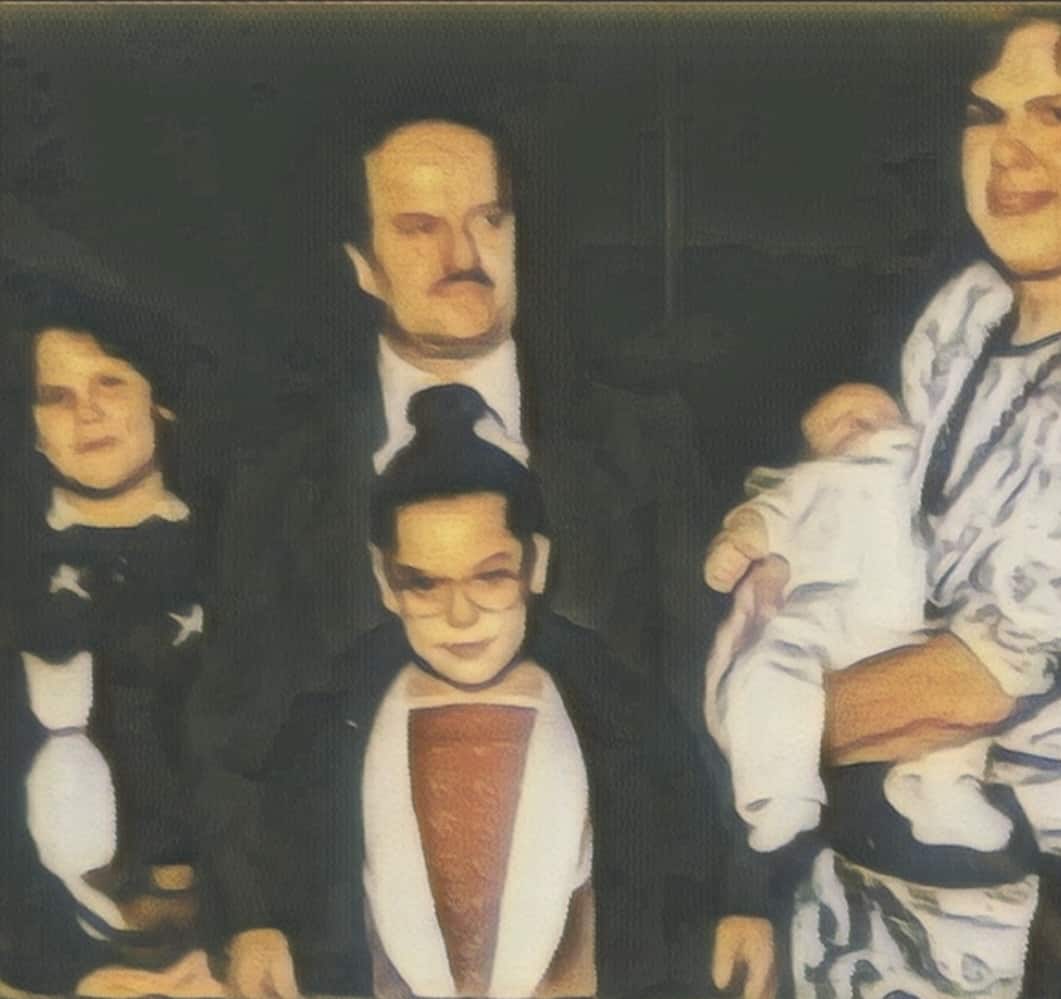

Feature photo unfiltered. The looks on our faces say so much.

In the last two years I have taken several multiple-month stints to go back home and care for my ailing parents. My Mom had heart surgery to replace several valves. She had a watched aortic aneurysm for years, and it had finally hit the ‘fix it’ threshold of 6mm that they were waiting for. Us Slovaks are built like tanks. It was a major “crack your ribcage and open you up” procedure that forced her to need assistance with daily living: bathing, getting up/ down, preparing meals, etc. It was hard to see someone so used to be capable and independent humble themselves to accept such help. She never asked me to come. She didn’t need to.

This was during the end of 2020 COVID wave and her doctor recommended she NOT go out to cardiac rehab, so I worked with her at home. I understood how to test and try and build capacity, and we didn’t need to be with a ‘professional’ to make that happen. My Mom didn’t need an electrician to figure out how to rewire broken ceiling fans. I didn’t need a cardiologist or pulmonary therapist. We trusted that we could find a way. And we always did.

When my Mom was back to functioning, and could perform daily tasks on her own, I returned back to Oregon. When they no longer need you, you can return to the life you built for yourself.

At Christmas of 2021, I got off the plane and saw my Dad and immediately said, “You look like sh*t.” He needed to know I wasn’t joking or playing around. I asked if I could take him to the Emergency Room to get checked out. We did, and he got priority and was seen almost immediately. His blood sugar was out of control, his white blood cell count super low, and he had three liters of fluid removed from his abdomen. He was under observation for three days, until he was stable enough that the overworked and overwhelmed ER department at Palos Hospital said he could go home for Christmas Eve.

He arrived weak and with a walker, but tried to have good spirits. No way he was going up the stairs. It was about 8p. We put him in a large cushy chair with an ottoman and let him sleep. 3a the dog starts barking. My Dad is on the floor speaking in tongues. He’s 230 pounds. I could get him up but when I wrapped my arms around him he said, “Ouch.” I didn’t want to hurt him, and he was not coherent. We called the ambulance. Three giant firefighters got him on a gurney and took him back to the Emergency Room.

There was something about being there during all this that made me naturally take ownership. I fielded calls from relatives and got out updates. I checked in with and was the point person with doctors. I served as the contact with the social worker who agreed that a nursing home (rehabilitation facility) was a necessary step before returning home. He had contracted COVID during his first hospital visit and had trouble breathing. He went on oxygen for weeks. We had a home set delivered and I had to learn how to use it. I prepared.

I had decided that I would take an indefinite leave of absence to return home and care for him. The indefinite part was the ultimate sign of in-it-ness. Being an excellent worker, he thrived on being told what to do. Without that direction, and feeling ill the last couple of years, he just sat. He watched TV, came down to eat, then went back to watching TV. He no longer drove because he got into an accident in which he got sued and the case was still pending. His favorite thing to do post-retirement was to go to grocery stores and find deals. He couldn’t even do that any more.

Please remember that my father didn’t know how to live. He had no hobbies, and was in such a state that he mostly wanted to be left alone when friends or relatives called. The discomfort was familiar. If he left or did anything out of the ordinary (AKA adjust from nothing) things would likely get worse. He learned the incredibly difficult lesson that having money saved and being responsible all your life doesn’t equate to having care when you need it. He’d have to pay for it, and paid care is not the same as willing and wanting to care.

I saw myself forty years from now as I looked at my Dad and realized his fate. I also knew that I would not have a me. As much as I understood what care was and why it was of such fundamental importance, I refused it. But I could give it. What to do and how to offer it came so easily to me. There was no plan. I would just be with him, cook and bring him meals, ask questions, listen, test out his capacity on little tasks, find out who he was and what he liked.

His time in the nursing home was motivating. Being left on a makeshift toilet for hours and not being able to do anything without someone coming to assist you makes you really want to get out of there. It makes you recognize that worse exists and if worse exists then so must better. He wanted to get better. He wanted to try. He built himself up through the random and playful challenges I set out for him.

As he gained belief and confidence, he wanted to learn and be shown. How do you make oatmeal? How much goes in the cup? Where do you find the cup? Where is the oatmeal kept? If there was routine and structure he could perform. He was an excellent worker… After some weeks of getting it right, then he would start to take ownership. I’m going to add some strawberries today. The crunch of the celery. Perhaps some nuts. He was building upon a foundation of ‘the right and healthy thing’. He was good, so now he could find better (and make the habit personal and more enticing).

He wanted to try the gym so we visited the rec center and found out we could both attend for free via the Silver Sneakers program. He LOVED not having to pay for. I gave him a few things to try and went with him as he tried it. After locating and communicating feels, I adjusted things. We tried and tried and tried and tried. It was through conversation that I taught him how to tell if it was beneficial or not. He was so used to pushing through and effort being the marker of success. He had to learn how to sense and decide whether to be done or change something. His obedient question of “What’s Next?” eventually turned into “I’m going to do (X).”

We used the same gradual release of responsibility to return him to driving. His coordination was improving immensely. We both began to trust his balance and timing and foot placement. I asked him if he wanted to drive around the neighborhood. Then to the gym. Then back from the gym. Pretty soon he just claimed the driver seat. This is how care works. It is not conditional, or demanding. It sits with, gets to know, and attempts to make improvement an internal ecosystem that can invigorate itself.

Once he could get around by himself, and had a solid grasp of routine, I booked a flight home about a month out. My father had learned how to care for himself and regain his independence. He was participating in life again, and his change in demeanor was not lost on my mother. They are coexisting harmoniously, as they have learned to better communicate and understand one another. I have returned to the life I built for myself, but this experience has made question so much. Relationships are vital to health, whether you choose to believe it or not.